Professional Ethics

Soon after my return to Hong Kong in 1984, I was shocked by the lack of sensibility toward the practice of professional ethics within the local cultural field. At that time, it was not uncommon that an art critic would take money to write a nice review of an exhibition ( we called it ‘eel writing’ 鱔稿 in Cantonese in those days). Fortunately, such practice is gradually dying down, but other forms of violation continue. One disturbing example in recent years was a case in which a known Hong Kong critic/curator collected the works of an artist whom he enthusiastically promoted through writing and curating at low cost or no cost. Soon after the death of this artist, he continued to actively promote the artist then put up his collection out to auction houses for profit. How could one trust his writing or curation when there was a hidden agenda?

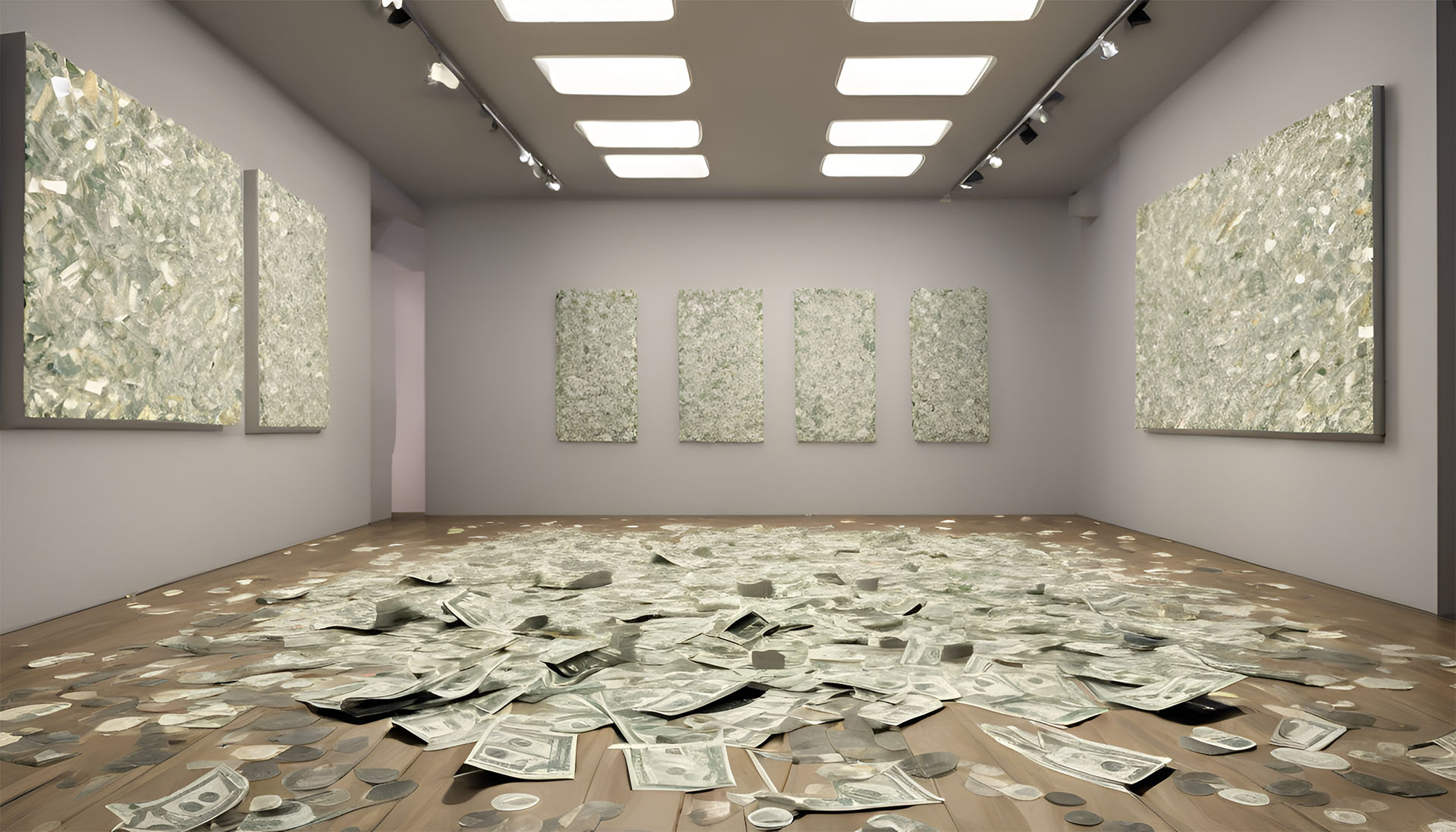

At a time when the art market dominates the art world, it is not surprising that some members of the art circle look at art from purely a profit-making perspective. During the interviews of applicants to our MACM programme, we came across applicants expressing their wishes to learn more about art marketing and brand building because their goals were to work in auction houses or engage in some sort of art marketing. It is fine to be an art dealer or get involved with the trading of art. The ethical issue arises when one pretends to be purely involved purely an art activity with no financial agenda on one hand, but on the other, taking advantage of one’s professional position to get personal goodies out of it.

Due to the rapid growth of the art market in the early 21st century in China, it was not uncommon curators got involved with art dealing. In fact, I was asked several times by friends from the West to find out whether some curators they worked with might be involved with art dealing. I heard horrifying stories in those years that some curators demanded to be given some of the exhibits afterward for sale as commission.

A less ugly but equally disturbing abuse of a curator’s role is to allow sponsors to overshadow their exhibitions. In Beijing I remember seeing automobiles placed right in the middle of an exhibition sponsored by the automaker. It is a general rule that no products relating to the brand of the sponsor are to be displayed inside the exhibition. In Kuala Lumpur, I saw a similar display of cars in an art exhibition as well. Years ago at an exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, the brand products of the sponsor were displayed as exhibits, and the sponsor’s logo appeared everywhere in the venue. Of course, we should not naively believe that a commercial sponsor has the kind heart to use its corporate money purely for the support of art. It has every reason to try to get the maximum publicity through its sponsorship. On the other hand, for the exhibition organizer, financial support is always appreciated, but it must not override the artistic integrity of the exhibition. Subsequently It is not acceptable to compromise thus transform the exhibition and turn it into a semi-commercial promotion.

Professional ethics in cultural management is a complicated and somewhat not too clearly defined practice. However, it is essential for the professional growth in curatorial practice and in the running of a cultural institution. I will elaborate more on this in my next piece of writing.

Oscar

Oscar Ho is Adjunct Associate Professor of Cultural Studies, CUHK. He was formerly the Director of the MA in Cultural Management Programme (2006 – 2020). Visit https://www2.crs.cuhk.edu.hk/faculty-staff/adjunct-professors/ho-hing-kay-oscar

*Image is generated by AI